Stories to smile about…

Laughter at Georgian Bay? Certainly! Why not? Did you know that the very first book to win the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour in 1947 was about the Bay?

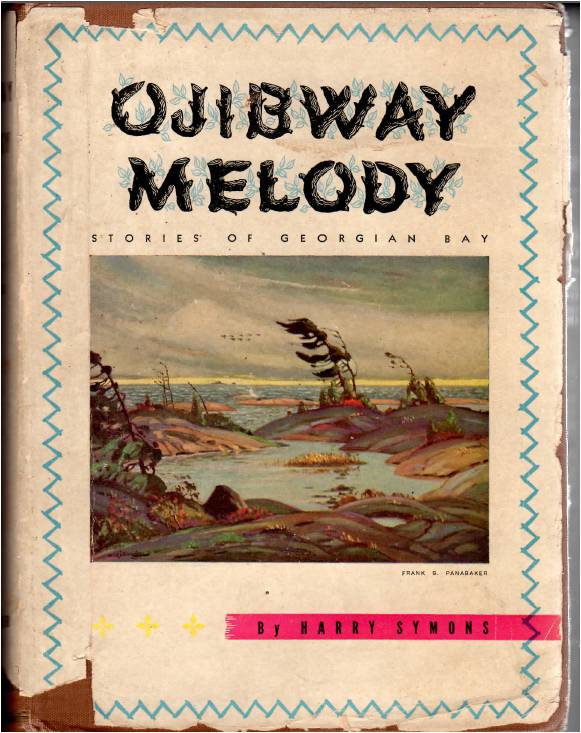

It was Ojibway Melody by Harry Symons, about cottaging in the Pointe au Baril area in the early 20th Century. The Ojibway Hotel there is mentioned often, as are the Ojibway people of the nearby First Nation, and so lend their name to the title. Having spent a couple of my youthful summers in the Fifties working there, I was drawn to this book many years ago.

Apparently my sense of humour was still relatively undeveloped though, because I was not impressed with Symons’ chatty style and self-deprecating humour. I wanted facts, information, background about that part of Georgian Bay where I had laboured with, and for, some very fine people. Just now, many decades later, I have re-read Ojibway Melody and realize that it had what I was looking for, just presented in an unfamiliar, intentionally entertaining way.

Harry L. Symons, born in 1893, was the son of an architect, presumably raised in Toronto but with ties to the northeastern United States as many cottagers had in those days. With the outbreak of World War 1, Harry entered the fray, became an ace fighter pilot and survived to become a businessman and writer of at least six other books of fiction and non-fiction.

Ojibway Melody humourously traces the trials and joys of a family reaching, opening, enjoying, and finally closing for the winter their cottage on an island in the Pointe au Baril area in the first half of the last century.

Having a similar family history a bit later in the Honey Harbour area, I could relate to the events Symons describes. Even the names of some cottagers and business people were familiar to me from the Fifties. And some of my experiences at the Ojibway and Pointe au Baril were amusing at the time, perhaps even funny (see The iceman).

Yes, Ojibway Melody is loaded with smiles so I don’t doubt it deserved the Leacock medal. And in the more serious context of current times with more recent generations of Canadians, in my re-read of the book I was impressed with Harry Symons’ respect and affection for the First Nations (they were just called Indians back then) and his empathy as they try to share their lands with colonists’ descendants.

In fact the book’s Foreword is about a native fishing guide named Pete de Blue. The author begins his writing with a word portrait of this man as he provided for his Indigenous family the traditional way while introducing them to the non-native culture. It was a sensitive gesture for Symons, and set the tone for his references to First Nations throughout the book.

Harry Lutz Symons died in 1962. One of his sons, the late Thomas Symons, was the founding president of Trent University in Peterborough, and a former chair of the Ontario Human Rights Commission. Another son, Scott Symons, also deceased, was a controversial author of early Canadian LGBT literature.